Introduction to fluorescence microscopy

Fluorescence is a natural phenomenon in which following the absorption of light by a molecule (fluorophore), the molecule almost immediately emits a light (with a longer wavelength). The phenomenon has been deeply exploited in many scientific fields, here comprised microscopy. Fluorescence microscopy relies on the capability to excite and selectively collect the emission of samples previously labeled with specific fluorophores.

Ultra fast temperature shift device for in vitro experiments under microscopy

Wide-field fluorescence microscopy: zoomed at the atomic level

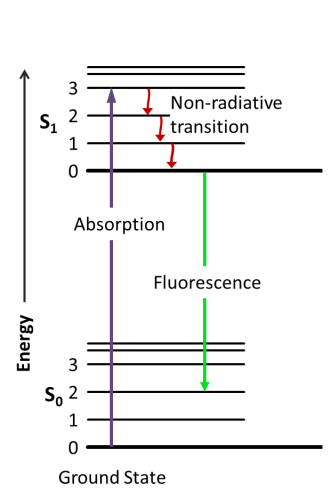

Fluorescence is the emission of electromagnetic radiation produced by the decay of an excited electron from the singlet state to its ground state (figure 1). The absorption of a photon with an energy of hѵ induces an orbital electron of a fluorophore to pass from the energetic level So to S1. S1 energy is equal to So + hѵ. Excited electrons in S1 typically relax by non-radiative transition before eventually ending up in a singlet state and decaying to the ground state by emitting electromagnetic radiation, typically visible light. While non-radiative phenomena (NRP) result in heat transfer to the nearby environment, the fluorescence emission generates a photon whit an energy that is equal to So + hѵ – NRPenergy. Thus the emitted photon in case of single-photon absorption has a longer wavelength (and thus less energy). This phenomenon, known as Stoke’s law, is rather important since as higher is the shift in wavelength, easier is to separate emission light from the excitation light by using filters able to exclude selected wavelengths (Fluo filters).

Fluorescence emission is much faster (10-8 seconds) than phosphorescence (minutes to hours) and disappears almost immediately once the excitation radiation is removed. For these reasons illumination and sample imaging should occur at the same time thus the necessity of applying filters to remove the band above a specific wavelength. The detection limit of an emitting sample depends on the ratio between the emission itself and the background noise. More the background is dark more the capability to observe fluorescence is high.

Since fluorescent emission is a statistically quite rare event depending on the fluorophore quantum yield, in a typical fluorescent microscope the light used to illuminate and excite the sample is several order of magnitude higher than the emitted fluorescence.

The need to strongly irradiate the sample has few drawbacks. Live specimens, especially when using shorter wavelengths to stimulate fluorescent emission, can suffer from photo-toxicity at high photon doses. The second aspect that comes from this high intensity irradiation is that the probability of secondary photochemical reactions increases significantly. Secondary photochemical reactions are the primary cause of decreasing emission among time. This phenomenon, called photobleaching, is a relevant issue when using some fluorescence microscopy techniques. Since the discovery of the photobleaching mechanisms scientist demonstrated that more than the intensity is the dose more implied in photobleaching. In other words a continuous milder irradiation might bring to more fluorophore loss of intensity than applying the same amount of photons in intense pulses. Among years several different microscopy configurations based on fluorescent microscopy have been developed. In the next paragraph we will list the most common fluorescent microscopy configurations.

Fluorescent microscopy techniques

Fluorescence is the core principle of several microscopy techniques developed in the last century. Techniques based on fluorescence microscopy have been applied to many different scientific and industrial fields; we will here focus on biological applications of fluorescence microscopy.

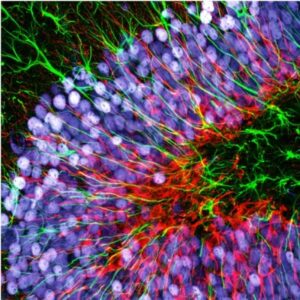

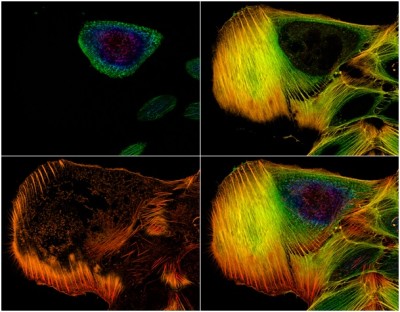

Wide-field fluorescence microscopy has opened many possibilities in life science especially considering the significant amount of molecules developed to “see” specific targets. By labeling specific cells structures or molecules scientists can visualize in real time changes in the distribution/conformation. Tagging cells according to the expression of specific surface ligands or the expression of selected genes is also possible and useful to monitor cells migrations, cell phenotyping etc. Cells genetically manipulated to express ionotropic channels sensitive to selected wavelengths allowed scientists to activate singles neurons (optogenetics) and map the functions of specific cells inside their neural circuit.

Three main approaches are used to properly label biological samples.

First approach uses natural or synthetic molecules that have a particular selectivity for specific molecules. Those molecules are often naturally fluorescent (i.e. Dapi, Draq5) or are chemically modified by binding a fluorophore (i.e. phalloidine).

Second approach is particularly used to visualize proteins of interest and is based on antibodies selectivity. In the simplest case an antibody against a specific protein is conjugated with a fluorophore and directly used to visualize the presence and distribution of a target protein inside or outside cells.

The third approach is based on genetically engineered cells that produce fluorescent proteins when specific genes are expressed.

Different factors must be considered when choosing the most convenient fluorescence microscopy technique. Those include: the desired spatial resolution; the dimension of the sample; the transparency of the sample; the concentration of a specific target; the presence of a strong autofluorescence background; the number of different targets; the nature (living/fixed) of the sample etc…

Hints on the characteristics of different fluorescent microscopy techniques with pros and cons can be found by clicking on the following links :

References

For more information please visit:

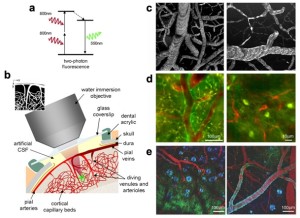

https://www.osapublishing.org/oe/fulltext.cfm?uri=oe-20-13-14534&id=238363

https://www.microscopyu.com/techniques/fluorescence/introduction-to-fluorescence-microscopy

http://zeiss-campus.magnet.fsu.edu/articles/superresolution/introduction.html